- Home

- Amy Bryant

Polly Page 3

Polly Read online

Page 3

Willam’s voice picked up speed. “They want you to pay attention to them, so you just ignore them. They want you to give them power, so you take it away. You pretend like they don’t exist, and soon enough, they won’t.”

“Maybe,” I said. The lump in my throat had gone away.

“If they do anything more I want you to tell us,” Mom said.

I nodded.

Two days later another note showed up in my locker. I didn’t read it, but instead made a show of tearing it up and throwing it away in the big trash can in the center of the locker commons, right in front of Stacy, Tammy, and Meagan. I was afraid to look over at them, but I hoped I came across like I didn’t care what they thought.

Things with Tommy remained relatively unchanged, except now we walked back from the trailer together after social studies. And Friday we planned to meet at the roller rink.

I wore my purple corduroys and Katie’s pink Izod shirt, and took my time with the curling iron. I put on purple eye shadow to go with my corduroys. In the car I rubbed at the black scuff marks on my skates. I wanted everything to be perfect.

Tommy was waiting at the door to the skating rink. Ben Waters wasn’t with him. I had thought about Tommy all day, pictured us talking and laughing like the other couples I saw at the roller rink. But now that he was in front of me I didn’t know what to say. I followed Katie to a bench to put on my skates while Tommy waited in the rental line.

“This is all kind of embarrassing,” I said.

“Pretend you don’t like him,” Katie said, lacing up one of her skates without bothering to look. “Or pretend you’re me. I’m not nervous at all.”

Tommy wobbled up, and together the three of us made our way out onto the floor. Katie and I got on either side of Tommy and gave him some pointers.

“Don’t try to stand up too straight,” Katie told him. “Keep your knees bent.”

“Keep your eyes on where you’re going—don’t look down at your skates,” I said.

Two hours later Tommy was skating without any problems. He wasn’t ready to skate backward with me during the slow songs, but he wasn’t threatening to fall down anymore either. He even managed to skate over to the snack bar and pay for a soft pretzel without losing control.

“Let’s get out on the floor, everybody. Three more songs and we’re out of here,” the DJ blared as we were finishing up at the snack bar.

We stood up. Katie hurried over to the floor, and I started to follow. Tommy tapped my elbow.

“Can I talk to you in private for a second?”

We skated over to the locker section as the dread gathered in my stomach. Two older boys I didn’t recognize were standing next to the lockers spitting dip onto the carpet, which already smelled like feet as it was. Tommy paused in front of them and then led me around the corner to the back of the lockers. My skates stuck on the carpet as I followed him into the corner.

All at once Tommy swung around and kissed me. He was taller than most of the other seventh graders and I was shorter than most kids, so he had to really lean down to get to me. At first I wasn’t sure if it was going to be a French kiss, but then I felt his tongue on my lips. I opened my mouth and frantically moved my tongue around.

After a minute Tommy straightened up and nodded at me.

“Okay,” he said.

“Okay,” I answered.

We lurched back across the carpet to where it was floor again. Tommy took my hand as we made our way back onto the skating floor, but dropped it once we got going, since it was a fast song. I couldn’t wait to tell Katie.

Monday before first period I found Meagan standing outside my classroom. Her shoulder-length black hair was feathered back into two perfect wings that met in the back of her head. I thought I might be able to slip by her, but she turned around to face me just as I got up to her.

“Me and Stacy and Tammy think you should read our notes,” she said.

Meagan held out another note, and I took it from her. She was wearing a thin gold bracelet that hung down several inches from her wrist.

I dropped the note into the trashcan Mrs. Gold kept by the door for gum. I started into class, and Meagan’s arm shot out in front of my chest.

“You better read it, Polly,” Meagan said.

A couple of kids looked over at us, and I felt my face get hot.

“I don’t feel like it,” I mumbled. I pushed through Meagan’s arm. I marched to my desk, fighting the urge to look back and see if Meagan or anyone else had picked up the note. Meagan followed me inside and stood at my desk. The other kids stared.

“You better think about what you’re doing to yourself,” she hissed.

The bell rang. I lowered my head, and Meagan disappeared back into the hallway.

Three weeks went by and there were no more notes, although they continued to give me dirty looks whenever they saw me. Katie joked that maybe someone else had quit the drill team, and there just wasn’t enough time to harass both of us. I knew that nobody on the team would quit now. The assembly was only a couple of weeks away.

Tommy continued to meet me at the roller rink on Fridays, and we stayed after school together a few times. We went out by the ball fields to French-kiss in private. I was glad that Tommy wanted to kiss in private instead of in the hall or in the locker commons.

He told me about his dog, Chance, a black Labrador mixed with some other kind of dog he didn’t know. It was Tommy’s job to walk Chance after school, but on the days we stayed after, Chance waited.

I told Tommy how Ben was always getting thrown out of Teen Living class and having to sit in the hallway for a time-out. Ben rode Tommy’s bus, and Tommy said that Ben was obnoxious but he was funny, too. I said I guessed that Ben was funny but I didn’t mean it.

Tommy didn’t like school, and he hated homework more than anything. Whenever I tried to talk about social studies, like how we should quiz each other on the state capitals we had to memorize, he got bored.

When we wanted to kiss we leaned up against the school between windows so nobody inside could see us. Sometimes we sat next to each other on the ground with our legs stretched out. We kissed at the roller rink, too, in the booths near the snack bar. It was easier to kiss at the roller rink because there wasn’t much of a chance a grown-up was going to catch us.

I was sure Tommy had noticed that I hadn’t started growing any boobs yet. I was sore under my nipples though, which I took as good sign, and I had pubic hair. Even though I didn’t have boobs I wore a bra like everyone else in gym class. Mom wanted me to wear an undershirt over my bra to help prevent colds, but I put my foot down. Undershirts were for little kids.

Two days before the drill team assembly I found a piece of notebook paper taped up to the outside of my locker. Written on the paper in blue magic marker was Tommy can’t get to second base. Underneath in bigger letters it said Polly Prude!!!!!!! Someone else had added She’s flat anyway in ballpoint pen.

I ripped the paper down, my heart banging against my chest. I hadn’t been to my locker in two periods. I prayed that the paper hadn’t been there that long. I dialed my locker combination through my tears. I was afraid to look up. I didn’t want to know if I was being stared at or if people were laughing at me. I was certain that Stacy, Tammy, and Meagan were somewhere nearby.

In Teen Living Ben Waters passed by my sewing machine and sang, “Tommy can’t get no, Satisfaction,” and some of the other kids laughed. Pat Barker shouted “Polly Prude” at me during gym, which I pretended not to hear. Derek Lindsey greeted me with my new name as I got on the bus.

“Shut your face, shorty,” Katie said, as I threw myself down next to her.

The next day Tommy came up to me after social studies class like nothing was going on.

“Can you stay after?”

“No,” I said. I rushed out of the trailer without looking at him. He called after me once, but didn’t catch up to me.

The next day was the day of the drill team assembly. Tomm

y tried to block my way as I came into the social studies trailer. I kept my head down and walked around him. He followed me to my desk.

“I didn’t tell anybody you were a prude,” he said.

Somebody behind us snickered. I pulled my social studies book and notebook out of my backpack and put them on my desk.

“I didn’t do anything,” he said.

I opened my book and looked down at a drawing of Abraham Lincoln. The caption underneath said, Abraham Lincoln wrote the Gettysburg Address on the train to Gettysburg.

Tommy went back to his desk, and after class I took my time getting up. By the time I got to the door of the trailer he was gone.

The drill team assembly was held during last period. I filed into the gym with the rest of my class and sat down in the metal bleachers. I didn’t see Katie or Tommy anywhere. Tina and Michelle, dressed in their cheerleader uniforms, were standing off to the side, chewing gum and surveying the crowd. They looked bored. I could see their bright blue eyeliner all the way from where I was sitting. I hunched down in my seat, hoping they wouldn’t notice me.

“Beat It” started, and the drill team filed out of the locker room in two purposeful rows. Everyone clapped. A boy on the other side of the bleachers shouted, “Beat Me! Beat Me!” and some people around me laughed. I smiled, even though I didn’t get it.

Fresh pangs of rejection ran through me. The routine looked neat from a distance. Twenty girls raised their knees high in front of them, like I remembered being shown. They held their arms straight at their sides, pom-poms hanging limply, and when they reached the center of the gym their arms began to mechanically move up and down, like they were independent of their bodies. Then they broke into two rows, weaving around one another. After that they went back into one row and flipped their pom-poms over their heads one after the other, so they were doing a wave. I was impressed.

Stacy, Tammy, and Meagan were together in the center, smiles frozen on their faces. Just as “Beat It” ended, the group dropped their pom-poms into two neat lines and shot their hands up into the air. Everyone clapped and cheered.

The drill team stayed perfectly still while the crowd thundered around them. Stacy’s and Tammy’s and Meagan’s high, swinging ponytails were the only movement in the line. It seemed like they were smiling right at me.

two JASON

Reston, Virginia, was a thirty-minute drive from Washington, D.C., a planned community sold to families not as a small city or a big town, but a “place.”

Reston was a place of public pools, community tennis courts, soccer fields, and tree-lined paths. Schools were designed to blend into the landscape, along with shops, libraries, post offices, and grocery stores.

We lived on Sunwood Court, between Trailleaf Court and Robinbend Court. We lived at the bottom of Sunwood, which sloped downward and was a perfect place to sled when we had a good snow. As in all Reston neighborhoods, there were plenty of kids to play with and, later, to babysit.

I wore braces for a year and a half. I permed my hair. I got promoted to the “gifted and talented” program at school. I grew nine inches in four years. Katie transferred to a Catholic school when ninth grade started, and I didn’t come out of my room for three days. We stayed best friends, but by the following summer it began to feel like an effort and we saw less and less of each other.

I redecorated my bedroom. I got my period. I became obsessed with the Ramones. My skin broke out. I learned to drive. I got drunk for the first time. I took up smoking. I went to my first rock concert, Iron Maiden. I let a boy I barely knew, Tom Jacobs, get to second base with me at a party. I cried for no reason once. Twice maybe.

I wished I had bigger boobs. I wished I had a boyfriend. I wished I were shorter. I wished I wasn’t so skinny. I wished I had blue eyes. I wished I looked like Michelle Pfeiffer in Grease 2. I wished I had a sibling.

I took French. “Quelle heure est-il?” I asked at the dinner table.

“Don’t they wear watches in France?” William asked.

“Don’t listen to him,” Mom said.

We were going to the movies. I was wearing my Megadeth T-shirt, the one with the skull that said KILLING IS MY BUSINESS on the front and BUSINESS IS GOOD on the back.

“I’m not leaving the house with her in that,” William said.

“Don’t listen to him,” Mom said.

I got a B+ on an English paper about MacBeth. We read the play aloud in class for two weeks, and I wrote about the scene where Lady MacBeth couldn’t wash the blood off her hands. I didn’t think Lady MacBeth was crazy. I thought Shakespeare was just trying to show us what happens when you push people too hard. If you make someone else commit a crime it’s the same as if you commit the crime, I wrote.

“It’s not an A,” William said.

“Don’t listen to him,” Mom said.

I hated high school. I didn’t play a sport or go see any sports. If you didn’t want to go to the homecoming dance, if you didn’t listen to Prince and wear Forenza sweaters, if you didn’t tease your bangs up and fold your jean cuffs in tight, you didn’t belong. Even if you did these things, sometimes you still didn’t belong. I made friends with other people who didn’t belong.

Herndon High School was large—more than three thousand kids. The popular kids were called bops. Cheerleaders were bops, members of the student government were bops. The jocks doubled as bops off the field.

Then there were the grits, who were also known as rednecks, or sometimes freaks or burnouts. The grits spent most of their time in the school parking lot, smoking Marlboros and listening to Lynyrd Skynyrd or Led Zeppelin in their pickup trucks. The grits wore jeans and denim jackets, and kept their hair long and shaggy. Beards were optional for grits, but they could all grow them with the ease of a thirty-year-old man. Grits tended to have Southern accents.

Everyone was afraid of the grits, except for the bamas. The bamas were tough black kids who listened to rap and were rumored to carry guns. Not all of the bamas were black. The Hispanic bamas were called spamas. Asian bamas were chamas. White bamas were whamas. The bamas carried boom boxes and yelled profanities at passersby.

Then there were the surf punks. The surf punks missed even more school than the grits did. The surf punks wore shorts in every season, bleached their hair, and did a wide variety of drugs. The surf punks had nicknames like Kicker, T-Bone, and Boomer. The surf punks liked to talk about wave conditions, even though Reston was several hours away from the ocean. All the surf punks were male, and they had a reputation for using girls.

There were skaters and deadheads and new wavers and metalheads and punk rockers and band geeks and drama geeks and regular geeks and art fags, but none of these groups, with the possible exception of the band geeks and the drama geeks, had the sheer numbers that the grits, bamas, bops, and surf punks did.

Fistfights were common at Herndon. The jocks fought the surf punks, the grits fought one another, the bamas fought everyone. No matter how many fights I saw, they always gave me the same sick feeling in my stomach and caused my legs to shake and my head to pound. Unlike most of my friends, my instinct was to run away from the fighting instead of toward it.

The first time I saw Jason Wilson, he was getting out of the backseat of Eric Graham’s car. It was January of junior year, and Theresa and I had come out to the parking lot to sneak a cigarette before first period. We shivered in our sweaters and shifted from foot to foot in the cold.

Eric introduced us. Jason was wearing motorcycle boots and a leather jacket over a Slayer T-shirt.

“Hey,” Jason said.

I didn’t know how I could have missed him before. It was his hair that I liked the most: blond, shoulder-length, stick straight, messy in places like he wasn’t aware of how great it was. His hair reminded me of the guitarist from Iron Maiden’s hair.

“Do you know that guy?” I said once Jason and Eric had gone inside.

“Who, Jason?” Theresa said. She tapped an ash to the ground with one of her lo

ng, red nails. “He’s a total dumb ass. I mean seriously out of it.”

“He’s cute,” I said. Theresa shook her head.

I didn’t see Jason again for a week. When I finally spotted him, walking by himself down the corridor, the same strong, quavering feeling that had washed over me the first time I saw him returned. It was like being at a rock concert, in that moment when the band first takes the stage.

As he got closer to me I saw recognition dawn on his face. I marveled at how his pale hair lay against his even lighter skin. When he came up alongside my locker he slowed down and pointed his finger at me and said my name, “Polly,” before continuing down the hall. Clinging to my locker door, I watched the back of his Venom T-shirt fade into the crowd.

This was what I had been waiting for. This unbearable moment; this boy slowing down in the hallway and pointing at me, saying my name. I felt like my real life—the one I was supposed to be living—was finally starting.

Theresa told me Jason was sixteen, the same age as us but a grade behind. I caught a glimpse of him crossing the parking lot from the window of my third-period trigonometry class. I watched him pull a pack of Marlboros out of his pocket as he wandered under the stadium bleachers. It left me feeling desperate and weak.

I wrote long entries in my journal about how I couldn’t believe he existed, right at my school. Songs that normally would make me switch radio stations became treatises on my behalf. “I can’t live, with or without you,” Bono sang, and I felt his starved resignation, understood how these things could come to be.

I made up fantasies about seeing Jason. He’d come up behind me in the hallway, get my number. In my daydreams he didn’t ask for it, he just said, “Give me your number.” In my daydreams he felt the same way I did, felt the connection between us when he said my name in the hallway that time. I varied my daydreams so that sometimes I ran into him in the parking lot or the lunchroom, but he always ended up with my number.

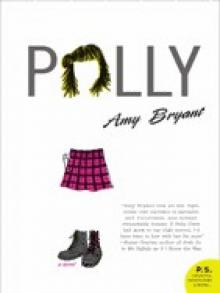

Polly

Polly